by Kassandra Lamb

While editing the book I’m releasing tomorrow, and especially while trying to pare down the scenes that beta readers and my editor said were dragging, I truly came to appreciate the importance of a finely honed description.

Descriptions in fiction are needed to ground the reader in the setting and allow him/her to visualize characters. But they can also bog down the pace and bore the reader if they are too long, and they can be jarring if they’re in the wrong spot. Today I’d like to share some thoughts about how to make descriptions concise and effective.

1. Why descriptions are so important. People’s brains tend to show a preference for one sense over the others when processing information, and which sense is in the lead varies from person to person. Some people are primarily auditory (30% of U.S. population); they process words and sounds far easier than what they see or sense in other ways. Others are primarily kinesthetic, i.e., movement and touch-oriented (3%). A rare few are primarily smell and taste-oriented.

But the largest group leads with their visual sense (65% of U.S. population). They need to be able to “see” the scene and/or characters in order to be “in” the story. Otherwise, it is just words on the page. They may still be entertained, but they will not be immersed.

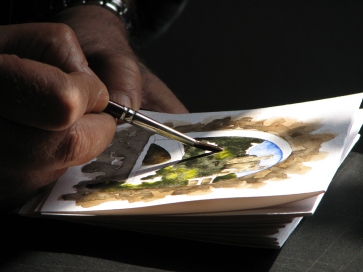

2. A few deft strokes will suffice. Descriptions are important but they don’t have to be lengthy. Readers only need a general framework, and their imaginations will fill in the details. One to three sentences will often do the trick.

If a description is feeling too unwieldy, ask yourself what the reader truly needs to know about that setting and/or which details set the scene the best.

In my new release, I had a too-long description of a living room in one of the draggy scenes. I decided that the crucial elements in that particular description were warm and colorful.

I didn’t need to mention the specific colors, nor were the highly polished mahogany end tables—as lovely as they sounded—essential to the scene.

It’s okay to let the reader assume things that are obvious, such as the presence of other living room furniture and lamps.

Here’s what I ended up with:

Kate smiled at the warm touches Maria had added to the room. Brightly colored pillows and a Guatemalan-patterned throw accented the beige sofa and two armchairs.

And yes, this is one of those times when a little bit of telling can be okay. “Warm touches” is telling, but it’s my protagonist’s reaction to the room so I can get away with it, and thereby keep the description short and sweet.

3. Use multiple senses, metaphors and similes, and characters’ physical reactions to make the setting description richer and more three-dimensional. Most people are at least somewhat visual, but not everyone, and engaging multiple senses makes the scene more vivid for all readers.

Bring in odors and sounds whenever you can, but also engage the sense of touch. Think about what you are trying to describe and then ask yourself how the character’s body might react to that stimulus.

The hot, humid air hit her like a wet blanket. She had trouble catching her breath. Her nose wrinkled at the stench of feces from the nearby dog park.

Watch out for filter words here, such as heard, saw, felt, smelled, etc. They tend to distance the reader from the setting and character. They can’t always be avoided, but ditch them when you can.

“It was a dark and stormy night.” (photo by Terry Robinson CC-BY-SA 2.0 Wikimedia Commons)

4. Use the setting description to evoke a mood. Decide what mood is right for the scene and then consider which details will create the desired reaction in your reader.

In the scene below, the protagonist is on a ride-along with a police officer. After a harrowing race through dark streets, she is left behind in the police car as the officer enters a building, in response to a shots-fired call.

Temporarily, her moments of sheer terror were over. She sat in the cruiser, its motor humming, blue lights reflecting off the wet pavement in front of it. Mist swirled around the car. The yellowish glow of the streetlights surrounding the parking lot created mini rainbows.

A good bit of the rest of the story revolves around this scene, but I left out most of the details that are important later on. It works to have her remember those details at those later points. Right now, they would not contribute to the dreary, somewhat spooky mood I am going for.

5. Re-ground the reader in the setting periodically. If a scene goes on for a while, and especially if it’s mostly dialog, the reader can lose track of where the characters are. They become what my editor calls “talking heads,” just floating in space. So throw in an occasional action beat—picking up a coffee cup from a desk or tapping the steering wheel—to re-ground the reader in the physical setting.

6. The basics are usually enough with character descriptions. Again, a few strokes—basic size, hair and eye color, approximate age, race. And again, some of these things can be implied or left to assumption. And others might not be important for that particular character.

A bald, jowly man, with pasty skin and a sizeable spare tire stood on her porch. His brown suit was a size too small and at least a decade out of style.

Bald and heavy implies middle-aged and pasty skin says Caucasian. If height isn’t mentioned, readers will assume it’s average. And in this instance, perhaps eye color isn’t needed. We have enough of a picture to move forward.

But if a physical trait is important later in the story, make sure it is mentioned in the initial description of the character, which brings us to…

7. Describe the character as soon after their first entrance into the story as possible. Otherwise, the reader may have created their own mental image of the person. Then when they are described later on, it’s likely to be jarring if the descriptions don’t match up. Jarring is almost never good as it pulls the reader out of the story.

This early description of characters is easy enough to do through the eyes of the protagonist, for everyone but the protagonist him/herself. Getting their description in there early on is challenging. You need to create a situation where the main character would naturally be thinking about or observing their own appearance.

You can have their image reflected in something, as long as this doesn’t seem contrived. You can also do this by comparison—the main character envies her friend’s petite figure, unlike her own tall, gawky one, or wishes she had shiny red hair like her nemesis at the office, instead of the mousy brown frizz she’s stuck with.

One of my sister authors at misterio press, K.B. Owen solved this problem brilliantly in her new historical mystery by having someone else make observations about the main character’s appearance, which then leads to introspection. This fit into the story naturally because the other character is called upon to help devise a disguise for the protagonist, a female Pinkerton agent about to embark on an undercover assignment.

She examined me critically. “My, how tall you are! And your dress…no, no, that will not do at all. You look like a…school-marm.”

I self-consciously smoothed my skirt. School-marm, indeed. I know that I’m much too tall and thin for the current fashion standard, my eyes are light gray rather than doe-brown, and most days I twist my blonde hair into an expedient topknot….

Well, perhaps there is a bit of the school-marm in me.

Compare and contrast can also work well in describing other characters through the protagonist’s eyes in a more natural way. If the character is well known to the protagonist, they might not normally notice that person’s appearance, unless it differs from the norm.

Kate notes one of her friends’ less-disheveled-than-usual appearance: Mac’s wiry body was decked out in his best clothes—a relatively wrinkle-free plaid shirt and only slightly baggy jeans. He’d even shaved at some point in the last twelve hours.

8. Use the description to show the character’s emotional or physical state and/or character traits. This makes the description more interesting and relevant.

Kate studied her reflection in the side window—her pale face, the dark mop of curls sprinkled with gray, crow’s feet around blue eyes dull with fatigue. What she would give for a good night’s sleep.

She’s exhausted, and now the reader is curious about why she isn’t sleeping well.

Rose’s five-foot, sturdy figure was clothed in her usual uniform of khaki slacks and crisp white, man-tailored shirt. Her black, silky hair was twisted into a bun on the back of her head.

Does this say her personality is no-nonsense? I hope so because that was my intention.

Okay, that’s all I’ve got. Do you all have any other helpful hints about descriptions?

And here’s the info on my new book. Available for preorder today and it goes live tomorrow! It’s just $1.99 until 2/22.

ANXIETY ATTACK, A Kate Huntington Mystery, #9

When an operative working undercover for Kate Huntington’s husband is shot, the alleged shooter turns out to be one of Kate’s psychotherapy clients, a man suffering from severe social anxiety. P.I. Skip Canfield had doubts from the beginning about this case, a complicated one of top secret projects and industrial espionage. Now one of his best operatives, and a friend, is in the hospital fighting for his life.

Tensions build when Skip learns that Kate—who’s convinced her client is innocent and too emotionally fragile to survive in prison—has been checking out leads on her own. Then a suspicious suicide brings the case to a head. Is the shooter tying up loose ends? Almost too late, Skip realizes he may be one of those loose ends, and someone seems to have no qualms about destroying his agency or getting to him through his family.

Kassandra Lamb is a retired psychotherapist/college professor turned mystery writer. She writes the Kate Huntington psychological suspense series and the Marcia Banks and Buddy cozy mysteries about a service dog trainer and her mentor dog. To find out more about her and her books, check out her website at http://kassandralamb.com

Thank you for such great advice on how to get the protagonist’s description in.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great post, Kass! So glad you shared these thoughts with us today. I was interested especially in the breakdown of how people perceive the world and process information. (I was once tested along those lines, the results were 50/50 visual/audio. They said that was relatively uncommon. ?) But I agree, you have to do your best to make your book work for as many readers as possible, and your tips are solid. (Of course, sometimes I go right ahead and insert a descriptive passage that’s longer than today’s norms, because it’s what I love to read, myself, in the right place. And because many of my readers are old enough to have been weaned on more descriptive prose, and they still seem to like it. I tell myself it’s a case of knowing the rules/guidelines before breaking them, but it’s probably more a case of being new at the game.)

At any rate, I’m sharing this post, and I’m keeping your advice in mind. Maybe I’ll get there, yet. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Marcia. It is a bit unusual to be close to a 50/50 blend but not totally unheard of by a long shot. I’m about 55% kinesthetic, 45% visual.

And one thing one can do with longer descriptions, and I think you’ve done this in some of your beautiful ones of the mountains, is to weave some action and/or characters’ reactions in with the physical details.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do try not to write paragraph after paragraph of scene description. Even I know I can’t get away with much of that. 🙂 But when I write about the mountains, it’s hard not to. I love the beauty of them SO much, I want everyone to feel like they’re standing right beside my characters. Always trying to learn to do it better and better. Your suggestions help.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is almost always a tough problem, Mary. It was actually my friend K.B.’s clever solution to it that first inspired me to write this post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, thanks to both of you, then. Too many protagonists spend too much time in front of mirrors telling us what they look like 🙂 It’s good to learn alternative methods.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Descriptions are so important for me when I read. I especially like when an author engages my senses,allowing me to immerse myself in a scene. And depending on the genre, I like varying lengths.

This was an informative and nicely put together post, Kassandra!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Mae. I get so frustrated when an author doesn’t give much of a description of the setting or the protagonist. Then the movie screen in my head is blank and I’m just reading words. I usually fall asleep. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like clean description. Not too much of it. I like to use my imagination. But, in order to do that, I do need a little from the author. 😉 I use #5 quite a bit and, also, #8. Love using description to “tell” about a character’s personality/state of mind. Great post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Sarah! Glad you enjoyed it. #8 is one of my favorite things to do with description as well. It is so economical to serve two purposes with one short paragraph.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Don Massenzio's Blog and commented:

Here’s a great post by Kassandra Lamb on the topic of brief descriptions in fiction via Marcia Meara’s blog

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome! Thanks for the reblog, Don!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Viv Drewa – The Owl Lady.

LikeLike